Blog

The Rise and Fall of Fandom, Part II: Mookie Betts

This is the second of two blog posts inspired by requests from readers. If you missed Part I, you can read it here. Part I was inspired by a request from my friend, Ben, from grad school. Part II, which is the piece you’re reading now, was inspired by a request from my friend Dennis, who I met in undergrad. Both are consistent readers of the blog, for which I thank you both! I would also like to apologize in advance for some of my language in this blog. There are a few expletives included.

Growing up, baseball was (and remains) my favorite sport and the Boston Red Sox were my favorite team. I lived and died with every game, and their abysmal 2012 season was one of the worst summers that I can remember. But there were plenty of good times too! My first season as a real, rabid fan was 2007. The Sox won the World Series that year, and they managed to rebound from the 2012 season to win again in 2013 (that team deserves its own blog post). They capped off the decade with ANOTHER World Series win in 2018, which, in retrospect, was a bittersweet penultimate chapter to my relationship with the team.

Mookie Betts holding the 2018 World Series trophy during the Championship Parade in Boston. Photo Credit to Stan Grossfeld.

The success of the Red Sox was an important part of my early fandom, but more than anything, the relationship that I have with the game is because of my dad. My dad is my best friend, my hero, and the reason that I am the way I am when it comes to baseball. So if I’ve ever annoyed you with my inability to shut up about baseball, blame my dad.

I was lucky enough to be born to a dad who loved sports and loved playing and watching sports with his kids. Some of my earliest baseball memories involve going to minor league games with my dad. We had two teams within about 45 minutes of my childhood home. One that played in Norwich (the Navigators, then the Defenders, and finally the Tigers) and one that played in Pawtucket (the Paw Sox). These games were much cheaper than the games MLB teams hosted and were a much easier commute than trekking up to Boston or down to New York. We would regularly attend somewhere around 5-10 games per year in the minors, but only ever one or two for MLB teams.

Me and my dad at the 2013 Single A All-Star Game in Norwich, Connecticut. Photo cred to Todd Kalif.

MLB tickets were then, and are now, exceedingly expensive. For the two of us to attend a game, usually at Fenway Park where the Red Sox play, it would run about $200-$300 for tickets and food at the game, plus another $40 for parking, plus four hours in the car round trip. Minor league games, all said and done, would be about $40. The $200+ at Fenway would get good, but not great seats. The $40 at minor league games would get you seats that would cost upwards of $1,000 at an MLB stadium. All of that is to say that the one or two games per year that my dad and I went to were extremely special.

One of the cooler things about the minor league games is that sometimes you would have the chance to see players before they made it to the big leagues. As the team in Norwich changed hands and levels, players there were less and less likely to be Major Leaguers. However, in Pawtucket, that team remained a high-level affiliate of the Boston Red Sox until 2020, when Rob Manfred decided to kill off 25% of all minor league affiliates. (For those who are unfamiliar, minor league teams serve as feeder teams for MLB clubs. Each MLB team had several affiliated clubs that would graduate players, step by step and level by level, to the parent club. Most players who play professional baseball will spend all or most of their career in the minor leagues, only a select few make it to MLB).

On one night in 2014, my dad took me to a Paw Sox game. I made it a mission of mine to get a ball signed by the Red Sox highest ranked prospect at the time, Mookie Betts. (Players in the minor leagues often sign autographs for fans--the practice is observed far less in MLB due to contracts with sports memorabilia companies). As he was running out to start his warm ups, I asked if he would sign a ball for me, he replied that he would when he was done warming up. As the time passed, I got distracted (with what, I have no idea), and wasn’t paying attention to when the warm ups had concluded.

“Hey kid! Do you still want me to sign?”

That’s what Mookie Betts yelled to me on his way back into the dugout. From that moment on, he was going to be my guy. No player had ever done that for me. Sure, a lot of them would sign if you asked, but often begrudgingly. Mookie made sure that he got back to me, even though he really had no obligation to do so. While Dustin Pedroia was my favorite player in the Majors, Mookie was going to be my #2 as soon as he made his debut.

Later that summer, Mookie made his debut with the Red Sox. On July 2, 2014, I was playing a travel baseball game that had been delayed because of lightning. While we waited out the delay, I was following the Red Sox game that was happening at Fenway Park concurrently. In just his 4th career game, Mookie started in center field for the Sox. In the bottom of the fifth inning, he absolutely launched his first career home run over the Green Monster in left. I was so excited that I jumped out of the dugout to tell my dad--who made it to nearly every single baseball game that I have ever played in--and we celebrated together before I had to get back to my own game.

Over the next three years, Dustin Pedroia and Mookie Betts shared the field for the Red Sox, but from 2015 on, Mookie was the better player. With Pedroia’s unceremonious end coming in 2017, all of my fandom was channeled into Mookie Betts. He was exciting, young, a great hitter, an exemplary fielder (even though he was brought into the organization to play second base but moved to the outfield in deference to Pedroia), and also short. He’s the same height as me, but he can dunk and also is better at bowling than I am at breathing:

From the jump, Mookie was obviously a different breed of baseball player. His 2014 season saw him play just 52 games, about a third of a season, and still put up 2.3 WAR. That’s a 6+ WAR pace! But, if you remember my article about Pedroia, you’ll know that the second year of a player’s career is often marked by regression. Well, in Betts’ second year, he put up 6.1 WAR. In fact, he has put up over 6 WAR in EVERY SINGLE FULL SEASON HE HAS PLAYED. That means that he’s been a top 10 player every year that he’s been healthy. Even in 2020, with a COVID-shortened 60 game schedule, Betts still managed an MLB leading 3.6 WAR in 55 games. A full season at that pace would have yielded 9.7 WAR, an MVP caliber level of production.

Mookie was a standout in 2016, producing 9.5 WAR and leading all of baseball in at bats and total bases. He ultimately finished second in MVP voting to Mike Trout, who put together one of the best seasons of all time. Not to be outdone, Mookie’s 2018 campaign saw him deliver a 10.7 WAR season. He led all of baseball in WAR, runs, batting average, slugging percentage, and took home his own MVP award. Mookie, like Pedroia, produced through every facet of his game. He was a beast on offense and a menace in the field. While not from his 2018 season, this catch from 2015 shows you the kind of fielder that he is. (It is also worth noting that he started playing outfield in 2014, before that he was a second baseman).

My favorite Mookie highlight from his tenure with the Red Sox is this grand slam that he hit as part of his 2018 MVP season. I’ll let Jomboy walk you through this one, though I do have to remark that on the TV broadcast, as Betts rounds second, the Sox’s broadcaster jubilantly yells “I’m telling ya! It’s time to party!” in a sing-songy, celebratory way. But that’s how it felt to watch Mookie do his thing on the 2018 Sox. I know this is a longer video, but I promise, you should watch it all to understand the kind of player that Betts was for the Sox that year. It was a team of destiny led by the best Red Sox player since Ted Williams led the team in the 1940s. It looked as if a new generation of Red Sox dominance was upon us, and Mookie was going to helm the franchise as it chased a dynastic run of World Series appearances.

Going into the 2019 season, there was a lot to look forward to for Boston fans. Betts, then just 26 years old, was leading a team of B-named outfielders (joined by Andrew Benintendi and Jackie Bradley Jr.) and everything looked rosy. Betts was still under the six years of team control that every player is burdened with at the outset of their career, but had entered his second year of salary arbitration, where he was awarded $20 million for his production on the field. With one year of team control remaining, Boston fans hoped that the multi-billionaire owner of the Red Sox, John Henry, would do what he should and lock up the franchise player to a long, expensive extension. According to the Fangraps WAR-Dollar calculator, which estimates what a player’s production is worth to a team on the open market, Bett’s had provided $230.4 million worth of production to the Sox from 2014 to 2018. In exchange, the Red Sox paid him $12.5 million. The top image below shows his worth to the Sox, while the one below shows his actual salaries.

If you’re a human with a job, or know someone with a job, or have ever had a job, that should make your stomach turn. Mookie Betts was compensated to the tune of 5.4% of what he produced for the Red Sox. $218 million was the difference between the two numbers. All of that went, essentially, right into the pockets of John Henry. And that does not account for the revenue made through merchandise, tickets, and food that fans purchased because they wanted his jersey or wanted to see him play. If the Red Sox paid Mookie Betts for an average of his production over those 5 seasons, he would have made just north of $46 million per year. So, when the time came to offer Betts an extension, a 10 year, $350 million (ish) deal would STILL BE A BARGAIN FOR WHAT THEY WERE GETTING. According to who? Not me. LITERALLY THE OPEN MARKET, THE VERY THING THAT ALREADY UNDERVALUES PLAYERS.

Anyway, Betts was never offered the opportunity to stay. Rumors persisted that the Sox offered him 10 years and $300 million, which is a steep discount for what he should have been offered, but Betts has denied that a $300 million offer was ever on the table. And it wasn’t as if Betts didn’t want to be a Red Sox leader forever, he’s quoted saying:

“We were looking for houses in Boston. We thought it was going to work out. I thought both sides were playing the slow game and it would eventually work out. We were negotiating, that’s what I thought.” About the franchise, Betts remarked “That was my team.”

“That WAS (emphasis added) my team.” Was. Why was it his team? Why isn’t it his team still? Well, my friends, it’s because Mookie Betts didn’t want to play in Boston. Oh, shit, I’m sorry. That’s just the rumor that Red Sox ownership started to make fans mad at their star player instead of at the owner that wouldn’t pay him. He isn’t still on the team because John Henry traded him to the Los Angeles Dodgers for essentially nothing. Why? Because they did not want to pay him what he was worth. He wanted to stay in Boston. He wanted to be a franchise icon. The fans wanted him to stay. The only people that didn’t want him to stay were the people that had to pay him.

“Why give Mookie money to make our fans happy when we could just take the money ourselves and be happy?” - Red Sox Ownership (probably)

As a young fan, I was absolutely dumbfounded. The best player that I had ever seen put on my team’s uniform was moving across the country to play for the Dodgers. And what did the Dodgers do when they got Mookie? They signed him to a 12 year, $365 million extension. Mookie Betts will be a Dodger until he retires. Since joining the Dodgers, Betts has maintained his elite level of play, but has somehow become more impressive.

Remember how I said Mookie Betts played excellent outfield for the Red Sox? Well he did it for the Dodgers too. Until they needed him to play second base and/or shortstop, two positions that he had not played in nearly a decade. What did he do? He was awesome at both spots and in the outfield. And at the plate. Since arriving in LA, he’s made an All Star Game every year there has been one, finished second, fifth, second again, and thirteenth in MVP voting, won four Silver Slugger Awards, and two Gold Glove Awards. He’s also added another two World Series victories, rings that every Boston fan expected would be won with our team.

Watching Betts succeed with another team wasn’t what killed my fandom. That’s part of being a sports fan. Your favorite players change teams, retire, or suck so bad that you wish they had done either of the first two things. That’s life. What killed my fandom was that, after trading Betts, John Henry raised ticket prices significantly. So significantly that games were now essentially out of reach for my family. Not only did he make the product shittier, he made it more expensive. Not because the Red Sox were in financial trouble, or because they weren’t turning a profit--they’re one of the most financially successful franchises in all of sports. He did it because he wanted more money. Because a number on the bottom of some fucking excel spreadsheet could get just that much bigger if he shipped out a generational talent. That’s what killed my fandom. Greed.

I do, however, take solace in the reality that the Los Angeles Dodgers, home to Mookie Betts and Shohei Ohtani (and every other good player not named Aaron Judge or Juan Soto), make gobs of money. According to Travis Sawchik--another favorite of mine--the Dodgers’ 2024 revenue was second in the league at $637 million, and they spent 67% of that money on payroll for their players. They also put together one of the most dominant franchises ever and won the World Series. (The only team that spent a higher percentage of their revenue on payroll was the Mets, who spent a whopping 102% of team revenue on payroll--shoutout to Steve Cohen, criminal, insider trader, owner of the Mets). The Red Sox came in third, with $557 million in revenue, but they spent just 40% on salaries. The Dodgers will continue to rake in cash because they cannot stop winning. They’re the best team in baseball now and will be for the foreseeable future and it’s fucking awesome. They pay their players fairly, they invest in their minor leagues, and they do just about everything right. Their owners spend money because a winning team makes money. Being a miserly piece of shit might save you some money in the long run, but it certainly isn’t worth the damage that you do to your franchise and its fanbase.

That is the miserable difference that ruined my ability to root for any team. Mookie Betts’ trade to the Dodgers showed me that the guy that owns your favorite team doesn’t want the same thing that you do. They root for their own finances, all else be damned.

To answer the question of “Why don’t you have a favorite team?” more succinctly:

I do not have a favorite team because I believe that every team, at one point or another, will break the unspoken, yet sacred, contract between fans and the team (by this I mean the team as an entity comprising ownership, management, and decisionmakers, not the players). This contract stipulates that I will spend time, money, energy, and attention on the team. In exchange, I can expect to receive a team that will try their best to win. John Henry did not try his best to win when he traded Betts in 2019. Hal Steinbrenner did not try his best to win when he let Soto walk this year. The only team that you can credibly accuse of doing everything in their power to win is the Los Angeles Dodgers. For now, Dodgers fans, I hope you bask in the sunshine of a mutually fulfilling relationship. You haven’t always had one with that team, and it will ebb and flow with the wants of the Baseball Gods.

So why am I a fan of the sport at all? Because one group of people do everything they can to win every single game: the players. The players live and die with their own successes and failures, they do everything possible to help the team that cares little for them. It is their will, athleticism, tenacity, and their personalities that make the games what they are. If you kept every single baseball owner in place but replaced all of the players with regular people, the game would be unwatchable. However, if you kept all of the players but replaced all of the owners with regular people… Well then we might even see the Chicago White Sox put up a fight.

The Rise and Fall of Fandom, Part I: Dustin Pedroia

The next two blog posts are both inspired by requests from readers. The first comes from one of my very good friends from grad school, Ben, and the other comes from one of my friends from undergrad, Dennis. Thank you both for being consistent readers of this blog, it means a lot to me!

I spent the majority of my childhood as a diehard fan of the Boston Red Sox, but my baseball fandom was born through a different franchise, the New York Yankees. My dad, the man who introduced me to the game and fostered my love for it, is a Yankees fan. As most children do, I absorbed my dad’s fandom and spent the early days of my interest in the sport as a Yankees fan. However, when I went to school, most of my friends were Red Sox fans. I did the unthinkable (and was later punished for it by the very team that I chose to root for, but more on that in the second iteration of this piece), I switched allegiances from the Yankees to the Red Sox.

One of the reasons that I fell so hard for the less successful of the two franchises was because of their second baseman, Dustin Pedroia. 2007 was a pivotal year for my baseball experience, it was the second year that I played organized baseball and was absolutely obsessed with the game. I loved watching it, I loved playing it, and I loved making my dad practice it with me until he told me it was time to go home. 2007 was also Dustin Pedroia’s first full year in the majors, and ended up being a World Series-winning-year for the Red Sox. Everything lined up for a young Max, rooting for his dad’s least favorite team.

If you know me in real life, you know that I am not very tall. I’m actually not tall at all. At 5’8”, I stand an inch shorter than the average American man. If you know anything about professional athletes, you know that they are often not comparable, physically, to a normal human. That heuristic stands true with baseball, even though you will get the occasional Bartolo “Big Sexy” Colon:

Those kinds of outliers are balanced out by outliers like Giancarlo Stanton, who is actually big and sexy:

One of the things that I most enjoy about baseball is that there are many, many different body types that can be present in the most successful of the sport’s athletes. While short baseball players aren’t quite as rare as short basketball players, the bigger and stronger you are, the better you will be. Dustin Pedroia was the player who kept my hopes alive that someday, I could be a professional baseball player too, he stood at a mere “5’9”” (I put that in quotes because he played at a time where if your listed height was 6’0” you were probably 5’10”, Pedroia was in the neighborhood of 5’7”). Pedroia himself has admitted that his listed height was a few inches north of where he actually stands. But I digress, Pedroia’s height was one thing, but the way he played baseball was something else entirely.

I will always remember Pedroia for the seasons that he spent flailing around on the infield dirt, legs kicking in every direction once he dove up the middle to backhand a sharply hit liner. He was a phenomenal fielder, but the way he did it wasn’t exactly pretty. He was all grit and dirt and hard-nosed baseball, it was the style of play you would expect out of a ballplayer his size. His style of play is often referred to as scrappy, and I feel as though the word itself is evocative of the way that he played. Something about his general attitude towards the game felt like a stray dog fighting for scraps, but when you stand back and look at his career, he was on a Hall of Fame trajectory until his injuries wore him out late in 2017. Playing in just 105 games that year, he was still able to put together 2.6 WAR, putting him on pace for 4 WAR, an All Star level season. However, over the next two years—his final two in MLB—he managed to play just nine games, collecting a mere three hits.

Until his unceremonious end, Pedroia was one of the most talented players in the big leagues. Any baseball player on the wrong side of 5’9” is going to have a soft spot in my heart, but one who managed to be among the best in the game? That is something special.

My memory of him begins in the 2007 playoffs. That season, I followed the Red Sox every day in the papers (I know, I know), I checked the box score of the games before walking to fifth grade. While Pedroia had an incredible year, he was not the Red Sock who I was checking the paper for every morning. Instead, I was enamored with Josh Beckett—the ace starting pitcher—and David “Big Papi” Ortiz, whose career in Boston elevated him to something of a folk hero to New England sports fans. I don’t remember watching many games on TV that year until the playoffs started. At that point my parents let me stay up a little later to watch the games.

In the World Series, against the Colorado Rockies, Pedroia tore the cover off of the ball. My clearest memory is his homerun launched deep into the night, as the first batter from the Red Sox to step to the plate in the game. You can see by watching the clip that he really had to put his all into his swing to get the ball out of the park.

But it wasn’t just a swing to hit homeruns, he put everything into every swing he took. Here’s a look at his hits from the postseason six years later, where the Red Sox took home their third Championship since the start of the 2004 season.

Something about the swing makes it look like a kid swinging his older brother’s bat, or a slightly older kid swinging his dad’s bat. But it was effective! And that’s all that matters.

After taking home the World Series trophy in 2007—along with Rookie of the Year—he followed up an incredible freshman season with an even better second year. This is definitely not a typical early career arc for any player, let alone the best. Often, when a young player comes up and sets the league on fire, it’s because pitchers haven’t faced him enough to know what he isn’t good at hitting. After his first year, there is a huge data set of any given player’s approach, and from that data set, teams will form their gameplan against him for the next year. For that reason, players that start their careers hot often have a lackluster year two (as well as some level of regression to the mean). In his second full year in MLB, Pedroia put up 7 WAR, leading the league in runs, hits, and doubles. That season marked his first All Star Game, Gold Glove Award, Silver Slugger Award, and an MVP. Through two years, Pedroia’s trophy case was nearly full.

Over the next seven and a half years, Pedroia added three more All Star appearances, three more Gold Glove Awards, and two top-10 MVP finishes. His 2011 season, the best of his career, came with a 9th place MVP finish due mostly to Justin Verlander’s absurd year and being slightly out-shone by teammate Jacoby Ellsbury.

I loved watching Pedroia, or “Petey”, bat because it was a funny thing to watch. But I loved watching him field because he was baffling. He got to balls that it didn’t seem like he had any reason to. Diving to his left and right, he was simply elite. But it always looked… how do I say this? Not ugly, but certainly not graceful either.

One play in particular has always been my favorite though, and to understand that one, we should take a look at what is arguably the most famous baseball play in the history of the game—for almost no reason. I also have to apologize to my dad for the next section. Dad, you aren’t going to like this and you can skip the next two paragraphs. The play, nicknamed “The Flip”, comes from the defensive “genius” of MLB legend Derek Jeter. Look, I can already hear the Yankees fans coming at me for that characterization, every defensive metric hates him, he was a bad fielder. If you want to make an argument that he was a good defensive shortstop, I’m all ears, but if it starts with how pretty it looked, you are wrong. The Flip is a play that is spoken about with deep reverence in baseball parlance, the play comes from the 2001 Playoffs, on October 13th. A base hit down the line looks like it will erase the Yankees’ 1-0 lead over the Athletics, especially when the throw from right field misses the cut-off man, waiting to relay the throw to home—done to improve accuracy and make up for the distance that the right fielder cannot throw the ball—but running down to the bouncing ball is Derek Jeter, nowhere near where you would expect a shortstop to be, who cuts the ball off and flips it to the catcher who tags the runner out at home.

I have two issues with this play:

I’m pretty sure the ball would have gotten to the Yankees catcher without Derek Jeter’s intervention.

Jeremy Giambi, the runner trying to score for the A’s, was safe at home. The Yankees’ catcher missed the tag.

Yankees fans are going to butcher me for that, but I speak the truth here at A Blog About Baseball.

Now let’s get back to that play by Dustin Pedroia. In the final inning of a tie game against the Texas Rangers, Carlos Gomez (a favorite of mine from the era) taps a ground ball to the Red Sox’s third baseman. It’s a slow roller, and Gomez has some speed, so it’s going to be a close play at first. The third baseman barehands the ball and comes up throwing. His throw is too far back into the runner for Mitch Moreland, the first baseman, to make a play on it. (Side Note: I remember Mitch Moreland being very good for the Red Sox, but I just looked at his stats and, it turns out, he wasn’t very good anywhere he played.) The ball ricochets off of the wall in foul territory, and Pedroia finds some wizardry of his own, barehanding the overthrow while sprawling out in shallow right field to orient himself just so, allowing him to throw the ball back to Moreland and retire Gomez. It’s better to just watch it:

I mean, that is everything that you would hope to see out of your franchise player. Unlike Jeter, he was exactly where he was supposed to be: backing up the throw to first. Unlike Jeter, there’s literally no way that Mitch Moreland could have gotten to that ball without Pedroia’s intervention. Unlike Jeter’s play, Gomez was out.

Want some more tie-game Petey highlights? Well if you’re still reading this, my assumption is that you do. Well, here, the Red Sox are tied in extra innings with the Los Angeles Angels. David Ortiz is at the plate, and the infield is shifted to cover the right side of the infield—because Ortiz was a dead pull hitter (he hit most of the balls he put in play to right field), just take a look at his spray chart from 2016 if you don’t believe me. You can see that he did almost all of his damage to right field:

Anyway, Ortiz was one of the most dangerous hitters in the game, and with the game on the line, there really aren’t many players you would rather have up at bat. But, Pedroia is standing on first base. Ortiz’s at-bat would be worth a lot more to the Red Sox if Pedroia was in scoring position (on second or third base). Pedroia wasn’t the fastest guy in the league by any stretch of the imagination, but he was quick and very smart. On this pitch, he steals second base cleanly. He then looks up, realizes that the shift has taken the third baseman far from the bag, and he just takes off, stealing third as well.

If you asked me to describe any player’s career in one play, I would have a tough time. Baseball is a complex and nuanced sport, to be successful, you need to be good at so many things that one play is unlikely to showcase the kind of player you are. The video above, however, perfectly summarizes Dustin Pedroia and his career. He wasn’t the biggest, or the strongest, or the fastest player on the field. But he was the physical embodiment of hustle and grit. I was never the biggest, or the strongest, or the fastest player on any team that I ever played on, but I always felt like I could make up for it by being as much like Dustin Pedroia as I could.

This blog is being published the day after the 2025 Hall of Fame Ballot is released. To make it to the Hall of Fame, players need 75% of the vote. To stay on the ballot for next year, they have to have at least 5%. Pedroia received 47 votes this year, good for 11.9% in his first year of eligibility. It’s not even remotely close enough to consider him a contender next year, or probably the year after. But it guarantees that next year, we’ll all have reason to revisit his career accomplishments again. And that makes me extraordinarily happy. Pedroia was a special player, not just to me and the legions of Red Sox fans, but for everyone who has ever enjoyed the game. He was an exceptionally firey player with an incredible amount of heart and determination. He was also excellent at baseball.

Pedroia retired with 51.9 career WAR, short of the heuristic 60 that often leads to enshrinement, but he accumulated the vast majority of that production before he turned 30. If you look only at post-integration second basemen (which you should, pre-integration statistics are dumb considering players were not playing against the best competition, just the best white competition) then Pedroia is the 12th best second baseman. Through his age 32 season—the last that saw a productive Petey—he was good for 49.9 WAR, 9th best. One can make a compelling statistical argument for Pedroia as a Hall of Famer, and so I will.

There are 16 players who played at least 75% of their games at second base that are currently enshrined in the Hall of Fame. Pedroia has a higher WAR than six of them. He also won the Rookie of the Year, MVP, a Silver Slugger Award, 4 Gold Gloves, a Wilson Defensive Player of the Year Award, and two World Series Rings (or three if you count 2018, but he only played 3 games all year, so…). That’s a pretty loaded trophy cabinet for someone who is going to miss out on the Hall.

Recently, one of my favorite real baseball authors, Michael Baumann, wrote a piece called In Defense of the Hall of Very Good, and it was essentially a similar piece to this but about his favorite player, Jimmy Rollins. Another short guy with exceptional baseball talent, Rollins and Pedroia were contemporaries for much of their respective peaks. Pedroia is closer to the positional requirements of a Hall of Famer than Rollins, who played shortstop, but both seem to fall a tier below induction. Baumann is excellent, I love everything he writes, and I am about to quote him liberally to describe how I feel about Pedroia:

“…while I consider the Hall of Fame to be the ultimate validator of general greatness, it’s borderline irrelevant when it comes to personal or even regional significance. And we don’t have to treat it as such, or to act like it’s a slap in the face if your favorite player (…) gets left out.” He goes on, “for players like Rollins (…) or Pedroia, it might be appropriate to name a stadium feature after a franchise legend, or let’s keep things simple: Retire their number.”

The Red Sox should make sure that no player ever wears 15 for their franchise again. Pedroia was a singularly brilliant player for them, bringing championships to Boston and creating baseball fans for life. For my entire youth baseball career (until high school and travel ball) I wore number 15 in honor of my favorite player. My dad made me a baseball nut, Pedroia make me a Red Sox nut. He is a franchise legend and probably would have been a Hall of Famer if not for injuries in his 30s. Boston destroyed a lot of fans’ rooting interest over the last few years (check my next piece for why) and it would mean a lot to a lot of people if they did offer this honor to Petey.

I do, however, disagree with Baumann. Rollins played until he was 37 and had four full seasons after his age 32 season. If Pedroia had had the opportunity to even be okay, say 3 WAR per year, for four more years, we’re talking about a Hall of Famer. And for that reason, I think Pedroia deserves to be enshrined. The injuries that cut his career short weren’t his fault, and it’s absurd that he will be punished for them. I’ve alluded to these injuries throughout the piece, and here I’ll address them. Though, it will be brief, to spare myself.

On April 21, 2017, Manny Machado slid—spikes up—into Dustin Pedroia’s surgically repaired left knee. Some say that it was an aggressive slide, but your host at A Blog About Baseball would call it a dirty slide. Going in spikes up can only mean that the intent was to injure.

Pedroia was quoted after saying:

“I remember when I got the first MRI after that play. A doctor said, ‘Hey man, you could ruin not only your career but the rest of your life with this injury. You tore all the cartilage off on your medial compartment on your femur and your tibia.’”

While he managed to play for most of the year in 2017, it was obvious to anyone who had watched him play that he didn’t look right. In the offseason, he underwent surgery to repair the damage done by Machado. Unfortunately, the doctor was right. Pedroia’s career was over after that season. Appearing in just 9 more games for Boston, Pedroia attempted multiple comebacks, but was never able to regain his playing health. Following a partial knee replacement in 2020—the second procedure that he got for the sake of day-to-day mobility instead of sports performance—he called it quits.

When asked about the play, Pedroia refused to blame Machado—though the author of this blog post places all of the blame on Machado—he instead said:

“That play could’ve happened my rookie year. When you play second base… like me, you hang on until the last possible second to get the ball because, you watched it: if there’s a slim chance at a double play, there’s one guy on planet Earth who could turn it. And you’re talking to him.”

There will only ever be one Dustin Pedroia. He was, and is, my favorite baseball player of all time. I loved watching him play and I’m glad that he will be on next year’s Hall of Fame ballot. I don’t think the writers will ever look on him as a deserving candidate, but I do hope that his number will be retired by the Red Sox. I also hope that, someday, the writers will see things my way, and put Pedroia where he belongs, in the Hall of Fame.

All for Juan

Well, 2025 is here, we’re all back from vacations, family outings, and general post-holiday malaise. Back to the grindstone, as the saying goes. Your favorite baseball blog author is also back after holiday travel, law school applications, and moving apartments, and I’m ready to start talking baseball again. The first thing I wanted to tackle in the new year is the thing that most of my non-baseball-enjoying friends and family asked me about over the last month or so: Juan Soto’s f*cking enormous contract.

In case you missed it, Juan Soto, 26-year-old outfielder, signed the biggest contract in the history of professional sports in December, a whopping 15-year, $765 million agreement to be the New York Mets’ rightfielder until he’s 41. That’s $51 million a year. Quite a lot of money for someone my age. Some of you probably saw that number and balked, maybe you even said something like “No one needs to make that much money!” or, “$765 million for a baseball player? What about (fill in the blank with your choice of doctors, teachers, nurses, etc.)?!”

Yes, this is a picture from his deposition for insider trading.

Look, $765 million IS a lot of money. But, I would recommend that you adjust the target of your rage to the man who made this contract possible, Mets’ owner Steve Cohen. Cohen is worth over $20 billion, and made his money as a hedge-fund founder. If you’ve heard his name before, it’s probably because he’s a crook, having paid the largest settlement ever for insider trading, $1.8 billion—more than double what Soto’s deal is worth. And that was just for the time that he got caught, he has been investigated for insider trading and racketeering on multiple occasions. He made his money in the same way that most billionaires do—by exploiting the working class and developing a parasitic attachment to the global financial system. Remember, we at A Blog About Baseball (both its author and its readers) see the ownership class as the enemy. When it all boils down, you, me, and Juan Soto, are cogs in a machine that makes money for other people. We are labor. When labor gets a bag, we should all applaud. Further, Steve Cohen has not become a multi-billionaire by making bad investments. For “Mets’ Owner Makes Bad Investments” please see this article about how their previous owner invested billions of dollars into the largest Ponzi Scheme in history. For all of you that were waiting for me to mention Bernie Madoff, there you go.

You may now find yourself saying, “Okay Max, I get it, billionaires bad, labor good. But why did he get the largest contract in the history of professional sports?” Well, my dear reader, it’s because Juan Soto is really, really good at baseball and he is really, really young, and baseball makes team owners lots and lots of money.

Soto began his career in 2018 with the woeful Washington Nationals. Just 19 at the time, Soto put together a very impressive season, accumulating 3.7 WAR over just 116 games. If you assume that he played a full-season’s worth of games, you’re talking about a 5 WAR player. How good is that? Well, in 2024, only 18 position players put up more than 5 WAR. From his first year in baseball, Juan Soto was one of the best players in the game. And he has only gotten better. In 7 MLB seasons, including the COVID-shortened 2020 season, Soto has put up 36.3 WAR. Since MLB was integrated in 1947, that is the 9th best WAR total among position players before turning 26. Of the names ahead of him on the list, only four are not in the Hall of Fame: Mike Trout, who is still playing and is therefore ineligible but will be a nearly-unanimous Hall of Famer when the time comes; Albert Pujols, one of the greatest hitters of all time who retired too recently to be in the Hall of Fame; Andruw Jones, who will probably be elected this year or next; and Alex Rodriguez, who will never be in the Hall of Fame because he took steroids and is one of the most unlikable humans on the planet. If you don’t believe me, here’s a picture of him kissing his reflection in a mirror.

A brief aside here for something that makes Juan Soto weird. Teams usually hang on to their young superstars for dear life. That is because of MLB’s arbitration system, in which players make almost no money for their first 6 full seasons in the league. For at least the first two years, but in most cases three, teams get to pay their pre-arbitration players the league minimum. These seasons are often some of the most productive seasons of players’ careers, and in many other cases, the only seasons that players will ever see at baseball’s highest level. The vast majority of MLB players will never sign a free agent deal. Soto is one of the lucky few who does. However, Soto has been on three teams already, the Mets will be his fourth. He was signed, developed, and made his debut with the Washington Nationals, won a World Series with that team in 2019 and put up four and a half seasons of excellent production. The Nationals, however, are one of the teams with terrible owners. They tore down a championship-winning team immediately after they won and traded several of their best players, including Soto, away. Soto then spent a year and a half with the San Diego Padres, a team with an excellent owner and a lot of talent on the roster. Unfortunately, the Padres’ then-owner, Peter Seidler passed away from cancer shortly after the 2023 season. It has been reported that he and Soto had engaged in contract talks and were interested in signing him to a long-term deal, but his untimely passing nixed those conversations, and the team prioritized fiscal conservatism over winning shortly after. The Padres then flipped him to the Yankees, where he was also excellent. The Yankees should not have let the Mets beat their offer, but they did. So off to a new team for the third time in four years.

What makes Juan Soto so special, and worth all of this money, is that he is one of the most talented hitters who has ever lived. Most of you have seen or heard of the movie Moneyball, which is one of my least favorite movies ever because it turned baseball from a sport to a field of profit exploitable by the likes of Steve Cohen. However, that movie DID teach a lot of people that “a walk is as good as a hit” (that is not ENTIRELY true, but for the most part it is). Juan Soto is incredible at walking. How good is he at walking? Well, walks are probably the most boring play in baseball. The pitcher throws four balls before the plate appearance is over, and the batter gets to go to first base for free. Well, it’s the most boring play in baseball UNLESS Juan Soto is batting. Why? Because if you throw him a ball, he’s going to dance right in your face. Look at this:

His Shuffle is so cool that El Alfa made a whole song about it.

The Soto Shuffle is just cool. He’s just a cool dude who turns boring plays into must-watch TV. He is constantly engaged in a cat-and-mouse game with the pitcher. Each one trying to outsmart and outmaneuver the other. As a result of his other-worldly ability to get on base, Juan Soto is an incredibly valuable part of a team. One of the reasons that he is so good at walking is because if you throw him a strike, he might hit one to the moon. (This highlight comes from Citi Field, which will be his home ballpark for his tenure with the Mets, I’m sure Mets fans that hated this when it happened are jumping for joy that he might do this a few hundred times in their uniform.)

I love this home run highlight. Soto crushes this pitch up and in. He gets his hands through to the ball in the blink of an eye and hits the furthest homerun that I have watched at Citi Field.

Okay, so what, he’s young and has been good, there are a lot of good, young players in baseball. Yes there are. But there are not a lot of young, elite players. Juan Soto is far more than just “good;” he is on pace to be one of the greatest players of all time. He is a generational talent and is so, so young. His skills are not based on physical attributes that will dissolve with age, like speed. He’s a great hitter with a great eye at the plate, two skills that tend to get better as you get older, he was the fourth-best player in baseball last year and we aren’t at his peak yet. According to FanGraphs wunderkind Dan Szymborski, Soto projects to be worth 65.8 WAR over the life of the contract (that’s the 50th percentile outcome, it could be better or worse). That would put him over 100 WAR for his career. Since integration, only 8 players have put up over 100 WAR. If Juan Soto hits his 50th percentile projection, you’re talking about one of the ten best players EVER. Even if you only look at the total for his time as a Met, 65.8 WAR is enough to make the Hall of Fame even if you took away all of the WAR that he accumulated in the run up to that contract.

Szymborski’s projection system also includes an estimate for what a player’s production is worth to a team, and he found that Soto’s production would be worth about $720 million over the course of this contract if he hits his 50th percentile outcome. But that’s only his value as a player on the field, he also sells tickets, merchandise, food, and gets more people to watch Mets games on TV. He may very well be worth $1 billion to a team over the course of this contract, maybe more. More evidence to support that: the New York Yankees, the team he played with in 2024, also offered him an incredible amount of money: $760 million. Billionaires don’t like losing money, that’s how they got to be billionaires. Soto is a smart move for any team and Yankees fans should be pissed off that their owner decided to let Cohen pull Soto from them.

The bottom line here: Juan Soto is an excellent ballplayer. He’s going to be excellent for the next decade. He got paid what he deserved and we should all celebrate when labor makes a “fair” cut of what they produce. Those poo-pooing the signing, the money, and the circumstances that make them both possible have a lot to learn about labor and the labor theory of value before critiques begin flying. When you side against players making more money, you are—in effect—saying that you do not believe YOU are worth more than whatever you are getting paid. And if you believe that, I sincerely hope you reflect on the value that you provide to your company or your workplace and reconsider. Management will always do whatever they can to rob you of whatever value you create, that is how they make profit. Juan Soto will make the Mets much richer than the $765 million they are paying him. Every season he leads them to the playoffs, the team will make tens of millions more than if they didn’t. He turns that team from a borderline playoff team to a perennial contender for the World Series. Players like him make the batters around him better. Teams don’t want to pitch to Soto because he might hit a ball 520 feet:

So they have to throw strikes to his teammates, who are equally capable of some incredible offense:

This is a great signing for the Mets. Their fans should be happy. Fans of baseball should be happy too. For all of the years that we have been hearing about how our sport is dying—including from some owners, see this piece on the A’s—this is proof that baseball is doing okay. It also holds the possibility to attract new people to the sport, athletes who may feel the pull of the NBA or NFL and the salaries earned by their stars. Baseball and its fans love Juan Soto, we should love that he makes an absurd amount of money.

Are the Dodgers Ruining Baseball?

In a word? No. The Los Angeles Dodgers are not ruining baseball, despite what you might be hearing from everyone who likes baseball in your orbit. Yankees fans, yes, I am looking at you. But I’m also looking at fans of the other 28 teams who feel sick to their stomach over the Dodgers 2024 World Series victory and their recent signing of free-agent pitcher and recent Cy Young Award winner, Blake Snell.

This article is a little bit of a rejoinder to the last article I wrote over a month ago (whoops! I was applying for law school, but we are so back baby) about the Chicago White Sox’s abysmal 2024. We looked at, and made fun of, a team that is terrible and has no intention to change that. Now, let’s look at a team that has dedicated itself to beating the snot out of the other 29 teams and talk about why we should be celebrating the Dodgers, not denigrating them. This is not a “they hate us, ‘cause they ain’t us” issue that often befalls the incumbent champion of any season—except for the 2019 Nationals, the 2023 Rangers, and a few other champions that no one has taken seriously—this is a fundamental misunderstanding of who has the best intention of their fans on their mind.

To start, we should revel in the 2024 Dodgers season, a tour de force brought to you by a team full of some of the best and most fun baseball players I have ever had the pleasure of watching. The chart below should look kind of familiar to those of you who have been reading this blog regularly (shoutout to all four of you guys, y’all make my day). This chart shows the Wins Above Replacement (WAR) accumulated by all 30 Major League Baseball (MLB) teams in the 2024 season. WAR, as a reminder, is a statistic that estimates the value each player contributes compared to their team over the most readily available replacement player (considered to be a high-level minor leaguer, or bottom-of-the-barrel major league talent). Basically, if you are a “replacement-level” player, you are easily replaceable by your team. 0-1 WAR is a bench player, 2-3 WAR is an average starter, 3-4 WAR is a good baseball player, 4-5 WAR is an All-Star, 5-6 WAR is a great player, and 6+ WAR is among the best players in baseball. This year, 11 players earned 6 or more WAR. As for team WAR, this is a cumulative effort, taking into account all of the WAR that everyone who played for the team accumulated. This year, the Dodgers led the pack with 39.6 WAR, 5.6 WAR ahead of the second-place Arizona Diamondbacks, and 46.3 WAR ahead of the last-place Chicago White Sox.

How did they accumulate all of this WAR? Well it was truly a team effort, eight of their players turned in seasons that were average or above. Only five of their position players accounted for less than 0 WAR, and combined they only amassed -1 total WAR. A mark that was bested by 3 INDIVIDUAL players on the 2024 White Sox. But what the Dodgers truly benefit from is an embarrassment of top-end talent. 7 of their players put up over 3 WAR, which means that about a third of their offensive roster was above average. Those seven players were Max Muncy, Miguel Rojas, Will Smith, Teoscar Hernandez, Freddie Freeman, Mookie Betts, and Shohei Ohtani. I want to talk about the last three names, who were also the best three on the team this season. Each of them has an argument of being some of the best players ever, and Shohei Ohtani—in the humble opinion of this blogger—is the best player to have ever lived.

Let’s start with Freddie Freeman. He’s your favorite baseball player’s favorite baseball player. Aside from having one of the best smiles in the game, he is just one of the best dudes in baseball. He joined the Dodgers in the 2021 offseason, signing a 6-year, $162 million deal. In his career, he has amassed 60.7 WAR in just 15 MLB seasons. That makes him the 14th-best primary first basemen in the history of the game. He’s an MVP, a two-time World Series Champion, and a sure bet to make the Hall of Fame. He has persevered through tragedy, having lost his mother to cancer when he was just 10, and having seen his son, Max, hospitalized with Guillain-Barre syndrome which resulted in paralysis earlier this year. He missed 15 games this year between his son’s illness and a severe ankle sprain suffered at the end of the 2024 season. His 4.7 WAR would have been 5.2 had he played a full 162 games season. He also absolutely mashed in the postseason, setting a record for most consecutive World Series games with a home run, including this absolute missile of a walk-off grand slam (sorry, Dad!).

Now onto my second favorite player in baseball, Marcus Allen “Mookie” Betts. Mookie Betts WAS my favorite player for most of my teenage years. He was the right fielder for the Boston Red Sox until I was 20, which was also my favorite team until I was 20. His departure in a trade is the reason that I am no longer a fan of any MLB team, simply because I refuse to root for the interests of billionaires over the players that make the game as fun as it is. I digress, Mookie Betts is one of the best outfielders in all of baseball. An MVP winner in 2018 and a six-time Gold Glove winner, he has long been considered to be one of the best defenders in the game—to say nothing of his exceptional bat. So he must have had a great season in right field for the Dodgers this year, right Max? Right? Right?! WRONG! Mookie Betts was primarily a shortstop for the Dodgers! He played 65 games at short, 18 at second, and 43 in right. If you’re good enough to do that math in your head, then this sentence doesn’t matter to you, but that is just 115 total games. Mookie Betts started just 115 games this year, appearing in 116, and still managed 4.8 WAR. Over a full 162 game season, that’s 6.7 WAR. However, before his June 16 injury, Betts was on pace for 7.5 WAR. Playing a position that he had played just 16 times in MLB prior to 2024, Betts was on an MVP pace. He also made some slick plays playing positions that were new to him at the highest level of the game.

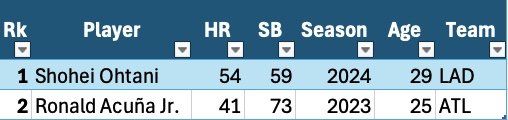

Shohei, Shohei, Shohei. If you know me, you know that I LOVE talking about Shohei Ohtani. While he is deserving of a blog post of his own—and he will get one—I’m going to try my best to keep things brief here. In 2024, Shohei Ohtani—the greatest baseball player EVER—put up 9.2 WAR and won the National League MVP. That is the BEST primary Designated Hitter season ever. To get a little weedy with y’all, Designated Hitters pay a price on their WAR for not playing the field. Positions like shortstop, center field, and catcher are considered premium defensive positions and are given additional WAR to account for the reality that they are defense-first positions. As an offense-ONLY position, DHs are penalized for not playing the field. And with this penalty, Shohei Ohtani had the third-best season in the league in 2024. Why is that a big deal? Well, Shohei Ohtani is not normally only a DH, he is usually ALSO a pitcher! He normally does something that no other baseball player has ever done. He is a top 5 hitter and a top 5 pitcher in the game when he is healthy. No one, not Babe Ruth or any other player, has managed that level of two-sided production in the history of the game. He is singular. He is the best. This season, Shohei did something that only five other players in the history of baseball have managed to do: record a 40/40 season. This feat refers to a 40 homerun, 40 stolen base season, and is considered to be an extremely rare feat of speed and power. Usually, good homerun hitters do not steal bases. Usually, good base stealers do not hit home runs. But Shohei didn’t JUST do something that has only been done five other times in the history of baseball. He did something that no other player has ever done. He is the founding member of the 50/50 club. Swatting 54 homers while swiping 59 bags.

Of players who have hit at least 50 home runs in one season, Shohei has 35 more stolen bases than second place—occupied by Willie Mays, who is one of the only players I would ever consider as challenging Shohei for the GOAT title.

Of players that have stolen at least 50 bases in one season, Shohei has 13 more home runs than second place Ronald Acuna Jr. (who is one of the other five 40/40 players).

Okay, so the Dodgers have a bunch of great players, and? And they have paid handsomely to acquire these players. Of the three players that I mentioned at length in this article, all three of them made their MLB debut with a different team. The Dodgers traded for, and signed, these three MVPs. That is something the Dodgers have done better than any other team in baseball—they have gone out and signed or traded for the best players in baseball. Last offseason, they committed over $1 billion to Shohei Ohtani and Yoshinobu Yamamoto ($700 million of which is going to retain the talent of the best player who has ever lived). They are paying six players in excess of $27 million per year. 10 players are getting over $10 million next year. That includes pitcher Blake Snell, who they signed to a five year, $182 million contract on Tuesday, November 28. This sent baseball fans over the edge, complaining that the Dodgers are “buying wins,” or “paying for a championship.” To that, I genuinely ask “So what?”

Arguing that what the Dodgers are doing is wrong is to say that billionaires should hoard their money to artificially dampen salaries. The Dodgers are simply paying the market value for talent, if you don’t like it, don’t be mad at the Dodgers, be mad at YOUR TEAM’S OWNER. Let’s pretend, for a moment, that your best friend at work is offered a massive raise to go to another company to do the same job they do now after trying to negotiate with their current employer for a better salary. You wouldn’t blame your friend for leaving, I’m sure you would leave for a better salary to do the same job too! Would you blame the company that offered them more money than your current employer? That also seems far-fetched. You’d probably think “Dang, I would also love to work for that company.” The ones who deserve blame in this hypothetical are your current employer, who was unwilling to pay market rate for your friend’s labor.

By turning our collective fan-angst on the Dodgers, we are saying that what we need is corporate socialism. We are collectively blaming the Dodgers for awarding laborers with a closer estimation of their value than any of the other 29 teams are willing to offer. In truth, every single major league baseball player is underpaid relative to the value that they create for their employer. You are too, that’s how profit is made. That the Dodgers are more generous than the other teams is something that should be celebrated, more money for laborers is a good thing. It is something that we should all strive for. The Dodgers are better at passing surplus value to their employees than the other 29 teams, it is that simple. They are the example that every team should follow. “Well why don’t they?” you might be asking. And that is a fair question. Why don’t other teams do what the Dodgers do? Is it because they can’t afford it? No, it is not because they can’t afford it. Would you believe it if a billionaire told you that they could not afford a $250 million annual expense from their company that earns, on average $378 million a year? They can’t afford a $128 million profit? That sounds dubious. That is to say nothing of the gradual increase in value that each team accrues every year, which has currently reached an average of $2.4 billion per team.

If you’re worried that the Dodgers are ruining baseball, you’re worried about the wrong thing. The people that own your favorite team can make your team better. Just as billionaires in the United States can afford to pay their fair share in taxes. It is the fault of decision makers far more powerful than any of us that billionaires are able to hoard their wealth in ways that continue to stratify society. Some billionaires are more willing to part with their dollars than other, contributing in a small way to the wealth transfer that our nation—and the world—so desperately needs. Those billionaires should be publicly encouraged and heralded. Those who bend the system to their wants are the ones we should vilify. If we don’t, they’ll get so used to our indifference—or praise—that they might run for President or try and cut the federal budget to a point where only they can afford to employ people, ensuring a cheap and desperate labor force where wages are depressed to the point where we can barely afford anything but the goods that the capitalist overlords produce.

The Dodgers are a capitalist organization. For that, they deserve blame. But they are the best example of capitalism available in the context of MLB teams. So let’s celebrate the Dodgers. While the rest of capitalism death-rattles its way through the second Trump Presidency, the Dodgers can be a fun escape for those of us unfortunate enough to have to deal with this bullshit.

The Woeful White Sox

Off the bat (pun intended), I would just like to say “thank you” to each of you that takes the time to read these pieces in part or in their entirety. I do love writing about baseball, and will continue to even when all four of you stop reading, but to those of you who text me or talk to me about what I write—it makes my day every single time. So again, and a million times over, thank you for supporting my little blog. Now, let’s get into the baseball.

As I am writing this, the Yankees and Dodgers have punched their tickets to the World Series, and Game 1 is tomorrow night. This postseason has already been one of the best that I can remember (and if you want to live through some of the games with me, you can follow me on Twitter @abaseballblog, I will definitely follow you back) and we are getting a matchup of the two best teams in MLB. Four of the ten best players in the game will all be on the biggest stage, representing the two teams with the biggest fanbases who have spent the most money to be the best. This is what every baseball fan should want. If you’re upset that your team didn’t spend as much as the Yankees or the Dodgers and you feel like that’s unfair, just remember that the billionaire that owns your team could spend as much as the Yankees and the Dodgers—and probably more—but they choose not to. And in honor of some of the best baseball of the year, I want to contextualize some of it for y’all by taking a look back at the single worst season of baseball that has happened in my lifetime.

Since 1998, the worst team in baseball, and one of the worst teams of all time, is the 2024 Chicago White Sox. That’s right! One of the worst teams of all time was playing baseball a month ago! And this team was not just regular bad, they were truly historically awful. In this article, we are only going to be looking at their offensive statistics, because they were truly abysmal. For the purposes of evaluating just how bad they are, I’m going to begin with a statistic called “WAR.” For those of you with regular lives and hobbies, WAR stands for “Wins Above Replacement” and is a basic value measure of a baseball player that takes into account their contributions offensively and defensively. In other words, the number of additional wins a team would accrue with a player over that of a replacement-level player, defined as a player who a team can add with minimal effort or cost. A general scale for understanding the statistic: negative WAR is very bad, 0-1 WAR is a bench player, 1-2 WAR is a below average regular, 2-3 WAR is an average starter, 3-4 WAR is a good player, 4-5 WAR is an All-Star, 5-6 WAR is a fantastic season, 6+ WAR is someone who might be among the top players in baseball. This year, just 11 players earned 6 or more WAR according to Baseball Reference and only 7 players accrued between 5 and 6 WAR.

One important thing to consider with WAR is that it is a counting statistic, meaning the more games you play, the more likely it is that your WAR will be higher than a player who doesn’t play as many games. Every game gives you additional chances to add or subtract value for your team. Of the 739 position players (non-pitchers) who accrued WAR this season, the lowest was Brandon Drury, who amassed -2 WAR in just 97 games for the Angels (which is its own impressive level of suck) and the highest was Aaron Judge, who amassed a whopping 10.8 WAR—an insane level of production. The most average player in MLB this year? Jake Cronenworth, who gave the Padres 2 WAR in 155 of 162 games. As for teams, the Dodgers led the pack with 39.6 WAR (thanks in large part to my favorite player, Shohei Ohtani and his 9.2 WAR) and you already know who was in last, the Chicago White Sox.

In 2024, the Chicago White Sox were the only team to produce negative WAR. They ended up with -6.8 WAR on their way to lose an unfathomable 141 games. Their final record on the year was 21 wins and 141 losses. For those of you who aren’t into baseball, there is a rule of thumb that every team will win 50 games, and every team will lose 50 games, it’s the other 62 that will decide whether you’re a good team or not. Did that rule hold up this year? Well, the next worst team, the Colorado Rockies lost just 101 games. 40 fewer games than the 2024 White Sox. The best team in baseball, the Los Angeles Dodgers, won 98 games this year. The gap between the White Sox and the Rockies (40 games) is larger than the gap between the Rockies and the Dodgers (37 games). Yes, you read that right. The difference between the best team and the second-worst team is SMALLER than the gap between the second-worst team and the worst team. The chart below shows the losses for every team this year, and the White Sox stick out like a sore thumb. If the 2024 season were analogous to a science experiment, the White Sox sucked so bad that we now have to rethink physics. Time stopped, gravity turned off, and the world stopped spinning.

Over their 162 game season, the White Sox averaged 3.1 runs per game. The next worst was the Tampa Bay Rays, who averaged 3.7 runs per game. But over the course of the season, that allowed the Rays to go 80-82. They won 59 more games than the White Sox. To achieve this level of awful, the entire roster had to do a lot of work to be so bad. The most valuable player on their team by WAR was Luis Robert Jr., a 26-year old outfielder who played just 100 games and produced 1.4 WAR. If he had played all 162 games and kept that pace, he would have produced about 2.3 WAR. If the best player on the White Sox played a full season, he would have been average. Every. Single. Other. Player. Produced less than 1 WAR. Take a look:

Of the 28 position players that appeared for the White Sox this year, just 12 of them managed to produce more than 0 WAR. That is awful. Remember 0 WAR represents a player that a team can pick up off of the scrap heap. The White Sox managed to turn in 16 different players who wouldn’t even belong at the top of the scrap heap. Oh, and number 25 on that list above, Andrew Benintendi, just got the biggest contract that the team has ever offered a free agent. They signed him to a five-year, $75 million contract at the beginning of 2023. Yikes. That’s a lot of money to spend on a player who puts up negative WAR.

I still feel like I haven’t quite contextualized how bad this team has been. So, let’s look at every season played by every MLB team since I’ve been alive. From 1998 until 2024, 30 teams have played 27 seasons each worth of baseball. That works out to 810 team seasons. The best team was the 2001 Seattle Mariners, they won a record 116 games with one of the most talented rosters in the history of the game. Their offense produced an incredible 50.4 WAR, over 10 wins better than the best team from this year. If you’re curious, the 2024 Dodgers are the third best team by WAR in my lifetime. Of the 810 seasons, the 2024 White Sox are the worst. Number 810 out of 810. The only team that is even in the ballpark (another pun) of suck is the 2019 Detroit Tigers, who put up -6.1 WAR on their way to lose 114 games. The third worst team, the 2010 Pittsburg Pirates, did not even manage -1 WAR. Only 5 out of the 810 teams managed to put up negative WAR over the course of a season.

Looking at this chart, it is unreal to see two things: first, oh my word the 2001 Mariners were insane; second, the tail end of that graph goes into the negatives in a profound way. When we look at just the 100 worst teams, the picture gets a little more clear, and a lot worse for the White Sox.

Even more incredibly, in THE ENTIRE HISTORY OF BASEBALL, only 128 teams have managed to produced 0 or fewer WAR. The 2024 White Sox are the 123rd team on this list. Only five teams in the history of the game have been worse than the 2024 White Sox.

This was a bad, bad year for the White Sox. And unfortunately for them, their owner is unlikely to spend in the upcoming offseason to improve the team at all. And with most bad teams, their fans can take some solace in knowing that their players are young and are likely to improve in the upcoming years. For example, the Oakland Athletics, who I wrote about for the first post of this blog, have an average age of just 26.5! That’s the fourth youngest roster in baseball. The White Sox, on the other hand, have an average age of 27.8, which puts them right in the middle of the pack of the 30 teams. This team is not going to get better, and with the fourth worst attendance in baseball this year, their management group isn’t going to be spending a lot of money.

For those of you who want to see how bad this team has been, here’s a great video of their low-lights from this year. It’s a tough watch, but hey, at least you’re (probably) not a White Sox fan.

Bullsh*t Bullpen Management?

Author’s Note: This is what many in the baseball writing industry call #GoryMath, it is inelegant, it is imperfect, but for the purposes of this piece, it’s good enough.

This piece is the first one that I’m doing about something that is currently happening in MLB. It is largely inspired by conversations I’ve been having with one of my real life friends about his favorite baseball team, the Cleveland Guardians. They are in the midst of their first meaningful playoff run since Barack Obama was President. I share the opinion of one of my favorite podcast hosts, Meg Rowley, who has stipulated—jokingly—that when the Chicago Cubs won the 2016 World Series against the Cleveland Guardians, snapping their 108-year World Series drought, the Cubs opened up a rupture in our timeline that allowed for the election of Donald Trump and the ensuing chaos. If the Cubs could win, anything was possible.

Anyway, tonight (October 17), they will be facing off in Game 3 of the American League Championship Series against the New York Yankees. The Yankees currently boast a 2-0 lead in the best-of-seven-series to decide who will go to the World Series. One theme that my friend and I have discussed throughout the Guardians run in the 2024 Postseason, including this series against the Yankees, has been their pitching usage. Their manager, Stephen Vogt, is in his first season as Manager of the club, and was playing Major League Baseball just two years ago. While there has been a trend lately of hiring young former ballplayers to manage teams, Vogt is exceptionally green for the role, having just one season of coaching experience between his career as a player ending and his role as skipper beginning. I, personally, do believe that the Guardians did better at hewing to the Selig Rule than the other hirings I wrote about last Sunday—for what it’s worth.

Now, it is important to have some context for this discussion before we get into the math of it all. In baseball, it is common practice to have two different roles assigned to your pitchers: starters and relievers. Starters do just what their name implies, they are the pitcher who begins the game on the mound for their team. It is expected that starters will pitch a majority of the team’s innings for that game. Relievers, on the other hand, hang out in the bullpen until they are needed to relieve the starter—you can see where their name comes from—due to fatigue, performance, or because the manager believes the relievers will be better against the upcoming batters than the starter. In baseball, at all levels, familiarity builds each time a batter faces a pitcher, so the more times a starter pitches to the same batter, the better one can expect the outcomes to be against the starter. Often, this effect is most apparent the third time through the batting order, which can occur at any point during the game depending on how many baserunners and runs the pitcher allows. The more baserunners and runs, the worse the pitcher is performing. Okay, basics are pretty much out of the way. Now we can get into it.

My friend and I text each other during Guardians games, and while I am not a Guards fan, I can appreciate the pain that he feels when things aren’t going well for his squad. One of the most frustrating things that can happen to a baseball fan, is an unforced error by the manager, and this manifests most predominantly in two ways, leaving a pitcher in too long, and taking a pitcher out too quickly. These decisions often happen on the margins and are much easier to see in hindsight, however, with Stephen Vogt this year, it has been incredibly obvious that he has a very quick hook with his starting pitchers. Last night I pulled some data from Stathead (pronounced “Stat Head”) to see if I could confirm what we were feeling watching the games. And I cannot believe what I ended up finding.

So far, in the 2024 MLB Postseason, starting pitchers are averaging just under 5 innings pitched (IP) per game—compared to about 5 and 1/3 innings during the regular season. However, Cleveland’s pitchers are averaging about 3 innings per game during the postseason! That is not good! That is very bad! For context, during the regular season, out of the 4858 player games started by a pitcher this year, 4426 games saw the starting pitchers go deeper into games than the Guardians’ starting pitching has this postseason. That puts the Cleveland starting pitchers in the bottom 8.9% of pitchers. Yikes. This is mainly an issue because it puts an undue amount of stress on the relievers on the Guardians, they are being asked to pitch way more innings than relievers on any other team. In terms of percentages, Cleveland’s starting pitching has lasted 30% less into games than the average team’s starting pitchers this postseason. They also pitched less than the average team during the regular season, but that difference was just 5%.

The graph above is a snapshot comparing the average team in the regular season and the average team this postseason to Cleveland’s pitching in the postseason and the regular season. You can see that in the postseason, the difference in innings is much larger than it was during the regular season. Otherwise, everything else looks about as you would expect. Where Cleveland was worse during the regular season, they have been worse during the postseason. But a few things stick out to me. Despite pitching 30% fewer innings and facing considerably fewer batters, Guardians pitchers are walking A TON of batters. In almost two fewer innings, they are averaging MORE walks than the rest of the postseason teams. They walked more batters than the average team during the regular season too, but only 7% more. In the postseason, that number has shot up to 11%. Below, you can see how that has impacted the WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) of Cleveland pitchers. They are allowing baserunners at a rate 43% higher than their postseason counterparts. That is awful.

I started this article expecting to confirm my assumption that Vogt was too quick to pull his pitchers. After looking at the numbers, I can’t blame him. I like this team, I do. Vogt is an easy manager to root for, the team is full of young players that have skills that aren’t found on many teams. Watching them play is really fun, watching them pitch is really not. I thought I could blame Vogt for being an over-zealous manager, too eager to treat every game as if it were a must-win. But it turns out, his pitching staff—or at least his starting pitchers—have been pretty bad. Stephen Vogt, I’m sorry, you are not the problem. Your roster is.

MLB’s Diversity Problem: Part I, The Baseball Bourgeoisie

Just a few of the greedy men, hell-bent on ruining the game.

I wasn’t planning on writing this piece until the offseason, especially given the majority of every baseball fan’s attention currently being expended on the playoffs but given the recent hirings of both Buster Posey and Terry Francona, now is as good a time as any. Last week I wrote about the self-inflicted advertising debacle that MLB created for itself and made reference to the reality that most of MLB’s biggest problems are caused by MLB itself. By “MLB” I mean the league in its entirety, an all-encompassing entity that includes the MLB League Office, the owners of the teams, and their front-office personnel. Effectively everyone that runs the league and the teams, “management” in other terms (or “the baseball bourgeoisie” if you prefer a more Marxist lens). This blog, like many that I hope to write, will hopefully show the three of you that read this exactly what I meant about baseball being a backdrop through which we can examine all of the socio-economic struggles that the United States has gone through and continues to go through. Each and every fight for equality, civil rights, and progress has played out in a much smaller way through the game of baseball.

Left, Farhan Zaidi. Right, Buster Posey.

Over the last week or so, this fight for equality played out in the two biggest personnel moves so far since the end of the season. The San Francisco Giants replaced long-time President of Baseball Operations (think CEO) Farhan Zaidi with their former face-of-the-franchise, future Hall of Fame catcher (and MVP, Rookie of the Year, and three-time World Series Champion), Buster Posey. This was followed in short order by the Cincinnati Reds hiring Terry Francona (also a probably Hall of Famer and two-time World Series Champion, though all as a manager) to replace their recently canned skipper, David Bell. In the case of the Giants, they replaced the first Muslim, first Pakistani-American, and first South-Asian American general manager/President of Baseball Operations (POBO) with a white man. Zaidi has degrees from MIT and UC Berkley and was widely respected as one of the best front office executives in baseball. He was replaced by Buster Posey, who is one of my favorite players of all time, but his qualifications are that he played baseball. That is a very old-school approach to the role of POBO, one that goes against the grain in the wrong way. Baseball is not a game of insiders anymore, POBOs are expected to be well versed in analytics, statistics, probability, finance, and business operations. The latter hiring was more of a one-for-one white-guy-for-white-guy hiring. Baseball managers are, unlike POBOs, still expected to be old-school baseball guys—former players who are a little more cerebral than your average ballplayer, but not an economist or financier by trade. They are the ones in the clubhouse responsible for wrangling 26 man-children, it is expected that they have spent considerable time around the game. But even that convention is now falling to the wayside, as Alyssa Nakken has been a regular coach for the Giants for the past few years.

Alyssa Nakken